A Few Ideas for Outstanding Academic Papers(1)

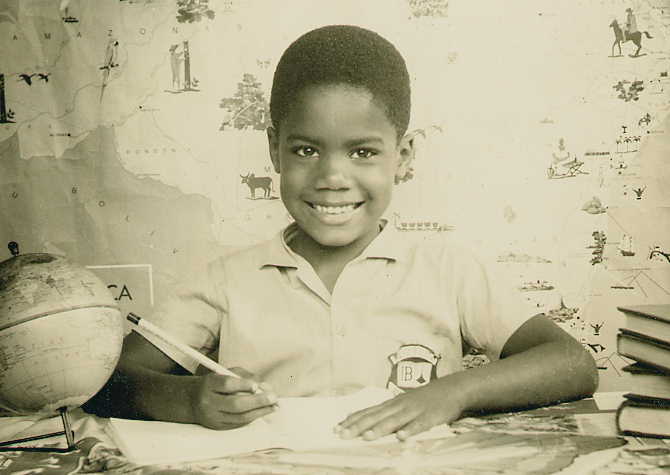

By Marcus H. Martins, Ph.D.

(work permanently in progress, 1994 - )

|

A Few Ideas for Outstanding Academic Papers(1) By Marcus H. Martins, Ph.D.

|

Writing is a critical professional skill, perhaps second to no other. One can have a wealth of knowledge and experience, but if he or she cannot express that knowledge clearly and concisely, that knowledge will not be imparted to others in an effective manner. Experts say that even those in the technical professions can expect to spend at least 30 percent of their work schedules writing memos, letters, proposals, reports, manuals, documentations, etc. That is why universities must require so many written assignments.

If you are not sure of what a writing assignment (or an exam question) means or requires, contact your professor A.S.A.P. Never follow your own suppositions. Contrary to popular--and false--beliefs, professors are hired to guide, to coach, and to mentor students, not to crucify them. Your professor's time is yours because, although indirectly, you help pay his or her salary. Just be sensible and remember that there are other students in your class besides you.

An outstanding (i.e., insightful, thought-provoking, exceptional) academic paper is a natural extension of one's life--or professional--experiences. I believe that most outstanding papers are written on topics their authors feel passionate about. A research paper must be a sample of the writer's intellect, and an invitation for readers to "take a peek into the writer's mind". Writing papers can be an unpleasant--to say the least--activity only when authors write on topics about which they have little or no interest.

We can say that on any given day we either "speak" or "think" ideas that might fill perhaps two or three 15-page papers. However, since an academic paper also requires scientific accuracy and novelty, it cannot be merely the regurgitation of an author's random thoughts. It requires--besides an author's feelings, inspiration, intuition, and wisdom on the chosen topic--a review of the existing literature on that subject and, when that is the case, the description and the analysis of the results of any tests, experiments, surveys, or interviews conducted by the author. Thus, an outstanding academic paper can never be written overnight.

In order to find a topic, answer the following questions:

Sufficient time must elapse from the first conception to the first draft, and from the first draft to the final version. During this time authors must use their imagination to conceive the following:1) What subjects, issues, problems, concerns, or questions occupy your mind most of the time on any given day? Don't "censor" your answers to this question. Write these answers on a piece of paper.2) From among the subjects on the above-mentioned list of most-thought-about subjects, which ones: (a) excite you the most or (b) upset you the most?

From the answers to question #2, choose the one subject you feel more prone to write about at this time--this is what your paper should be about. It must be a subject about which you feel passionate; something so attractive that you will research the subject with pleasure, regardless of the number of hours or days it will take you to write each paragraph.

A mere collection of quotations from other authors--or a simple restatement of their main ideas--should not be considered a "novel" (i.e., original or innovative) paper. On the other hand, when intelligent responses and innovative improvements, extensions or interpretations are added to the original authors' ideas (and if these original ideas constitute the smaller portion of the new writing) then we have what might be considered an addition to the existing body of knowledge.(1) what has not been--so far--thought of and written in regards to the subject; and

(2) what--from these yet unwritten thoughts--would be not only worthwhile being published but also appealing to a distinctive group of readers.

A "rule of thumb": When in college (and specially after college) don't waste your and your readers' time by writing a paper that could very well have been written by an excellent junior student in High School or in Seminary. If you need ideas to deepen your discussion, talk to your professor.

Researching is an art. It requires significant expenditures in time, commitment, effort, mental exertion, and sometimes, money. But once authors have chosen topics they feel passionate about, these expenditures will not turn their lives into living nightmares. In fact, passion turns the research process with all its sacrifices into an enlightening, enjoyable, and rewarding experience.

Once the author has decided on a subject or question to be addressed, he or she should:

(1) Check the existing literature to see what has already been written by other authors on the chosen subject.

(2) After becoming familiarized with the existing body of knowledge, the author must imagine what else could be written on the topic that could become a significant and important addition to this body of knowledge.

(3) Then, the author should use his or her intelligence to outline and develop what he or she is going to write. This is the stage in which the cleverness of an author--or lack of it--will be manifested. Here, the author's skills and ability will be used to:

- analyze data and events

- dream of possibilities still uncovered, especially in the case of complex problems still unsolved

- conceive hidden alternatives while either formulating or evaluating questions and hypotheses

- detect the original authors' and one's own biases and prejudices

- evaluate and critique the original authors' and one's own conclusions.

The title of a paper is an "invitation" to the reader. A well-thought and "catchy" title makes readers want to open a space in their busy schedules to read a specific paper--a must in today's information-overflowed society.

The chosen title must clearly reflect the issue or question being addressed in the paper. A title that does not accurately reflect the content of a paper will deceive the reader, who then will feel "betrayed" by the author.

From time to time ask a friend or colleague--including persons not familiarized with the chosen topic--to read drafts of the paper. All papers make perfect sense to those who are writing them; unfortunately, the readers' understanding of the text will not always coincide with the authors'. A highly recommended idea is to seek help at a college's Writing Center.

Your readers should never be distracted by spelling or grammar errors. Their occurrence sheds a negative light on your work and on yourself as a professional.

Check for spelling errors. Since all of today's best computerized wordprocessors contain a spell-checking subroutine, the presence of spelling mistakes is both inexcusable and unpardonable. It indicates that the author wasn't meticulous in his or her appraisal of the final version of the paper.

As a "rule of thumb," spell-checking should be done at least once a day, even during the early stages of the writing process.

Never print any document without running the spell-check sub-routine at least immediately before printing.

Check for grammar. If a grammar-checking program is not available, ask a knowledgeable person to help you with that.

Improving the Appearance of the Paper

All written materials should be "clean" and organized. Consider the following ideas(2):

The quality of the printout is a statement of how much the reader is important to you. Use a laser printer to print anything important or "official" (e.g., final version of a paper, letter to an editor, a fax, etc.)

You may use a dot-matrix printer in the case of documents of lesser importance addressed to at least "somewhat important" individuals, but always change to a brand new ribbon for such documents (keep one aside exclusively for these occasions).

Never present a computer-printed document with handwritings of any kind: names, titles, page numbers, phone numbers of good-looking neighbors, etc.

A suggestion: include a page footer (or header) that shows in small font:

Always ensure that the paper is attractive, meaning:

- the author's name or last name

- title (or an abbreviated title) of the paper

- page number

A paper exemplifies a piece of the author's brain. Thus, never turn in a paper:

- make it easy for readers to access information in the paper by making use of subtitles; that will also help in guiding their thinking process--thus decreasing the likelihood of misinterpretations

- make appropriate use of lists, tables, and a table of contents, especially in long reports

- use a page design that catches the attention of potential readers:

- avoid extra-long paragraphs; give readers some white space to "rest" their eyes

- Here is a "rule of thumb" (highly debatable) for paragraph length:

- double-spaced documents: ½ page long (maximum)

- single-spaced documents: ½ or ¼ page long (maximum) with one extra blank line between paragraphs and two extra blank lines before new subtitles or headings

- divide your arguments, analyses, or discussions into "logical segments" and design paragraphs long enough to deal with each of these segments

- Always turn in the paper already stapled or--when in professional settings or dealing with a very important subject--bound with an artful cover

- showing last-minute handwritings, since these would suggest to the reader's mind that the author was careless; in such cases, the reader will be on the watch to catch further unseen mistakes

- shabby, torn, or wet pages, which would suggest an inferior, or cheap work; when hand-delivering a paper, always carry it inside a folder or binder with a hard cover

Avoiding Accidents, Tragedies, Disappointments, and Lawsuits

Have someone intelligent (i.e., with a brain above the academic freezing point) read the paper--or a draft of the same--at least two weeks before the deadline. Check for the following problems:

Make an effort to print the paper--whenever possible--several hours or 24 hours before the deadline; but never, never print a paper within the two hours before the deadline--horrible things happen with computers, disks, printers, e-mail servers, faxes, and other electronic equipment and media in general as result of The Curse of the Late-Printing Document!

- plagiarism (i.e., no credit for someone else's ideas or statements)

- strive to identify the original authors (and their professions) of either quoted or paraphrased statements

- logical contradictions (e.g.: a=c; c=f; but at the same time, a <> f)

- unsubstantiated claims--i.e., statements without legal, scriptural, literary, theoretical, or statistical support (e.g.: a=c; c=f; therefore, b=g)

- simplism: common-place reasoning; oversimplifications; one-sided analyses; exclusion of complicating factors

- taken-for-granted expressions and conclusions--what is good for a "testimony meeting" or a political rally may not necessarily be considered acceptable (or even intelligent enough) in an academic paper; always be grounded on legal, scriptural, literary, or statistical bases (besides, one doesn't need to go to college to be able to put together a stream of clichés and sound bites)

- vain repetitions (a.k.a. "beating a dead horse")

- long quotations or long paraphrases of well-known pieces of literature or of scriptural sources--if you are writing a paper you should have more to say than the existing literature offers (otherwise, don't write it!)

- technical or professional jargon--which the reader is not obligated to know

- slang--which may cast an unfavorable light on your work

- Be careful with idioms and slang, especially in cases where they mean the opposite of what you are trying to say. For example: "incredible" means "too extraordinary or improbable to be believed." The fact that a word is commonly used does not make it correct for academic purposes--and if you were to use such words in a professional interview, you would be placing yourself in "hot water." Also keep in mind that slang is often used by individuals who don't have anything intelligent to say; so, use it only in jest or in otherwise necessary circumstances.

Additional Ideas for Papers on Religious Subjects

Not every title published by Deseret Book or Bookcraft can be classified as "teachings of living prophets." (Sorry, folks!)

There is a difference between "living prophets" and "living legends." Quoting President Gordon B. Hinckley, Elder Bruce R. McConkie, President Spencer W. Kimball, or Elder Neal A. Maxwell, weights far more heavily than quoting Hugh Nibley, Steve Covey, Gerald Lund, Chieko Okazaki, Janice Kapp Perry, or Marcus Martins (marcus who?)

Be very careful with "hearsay"--statements that often begin with the words: "a church leader once said ..." or "I heard someone say that her cousin told her that he heard that Elder 'so-and-so' had said in a luncheon that ...", etc. If you can't determine who said what, where, when, and in what context, then it is better not to use that quotation in an academic work. Statements like those may be satisfactory (with an extra dose of goodwill) in a fast and testimony meeting, but they will never be accepted in college writing.

Also be on the watch against the contemporary trend towards idealized, romanticized, pageantry-laden, music-filled, secularized, "fluffy" imitations of the gospel.

Timing of Official Pronouncements

It is also extremely important to take into consideration (and in some cases inform) the time of original statements. This is critical in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints because of the principle of continuous revelation, which makes revelations be "time- or age-sensitive." New revelations and authoritative interpretations or statements will frequently expand the meaning and consequently our understanding of previously published statements.

Quotes must refer directly to the central issue, not to matters that are peripheral to the issue being considered. Consider the following examples of critical issues (C.I.) and matters that can be considered peripheral (P.M.) to those issues:

C.I.: Atonement and Self-worth

P.M.: Christ is our BrotherC.I.: The Lord needs an organization

P.M.: The Book of Mormon is the keystone of our religionC.I.: Commandments are an expression of God's love

P.M.: We have living prophets on the earthWhen quoting scriptures, try to identify the authors of the statements. This will make your quotation become more "personalized," and it will help increase the efficacy of your argument.

So, instead of writing: "In Romans 1:16 it says ..."

Write this: "The Apostle Paul wrote: 'For I am not ashamed of the gospel ...' (Romans 1:16)"

It is a respectful policy to always refer to LDS General Authorities using the titles "Elder," "President," or "Bishop." Whenever possible and convenient, identify their callings at the time of the statement you are quoting.

In the case of non-LDS ecclesiastical authorities, identify their professions or their positions in their respective denominations.

Worldly Titles and Standards Applied to General Authorities

In my opinion, there is a hidden fallacy in the use of popular worldly titles and standards in an effort to "prove" the important role of living prophets. Consider the following statements:

Such honest statements in a certain way place Prophets, Seers, and Revelators on the same level of politicians, corporate executives, sport or entertainment celebrities, billionaires, etc. Yet, the sacred nature of their calling does not mix well with such worldly standards. Besides, the use of superlatives (e.g. "the best," "the greatest ...," "the most ...,") is a fairly common American cultural trait that besides being considered inappropriate in many cultures, is also useless and meaningless from a purely doctrinal standpoint."President 'so-and-so' is our hero"

"President 'so-and-so' is the greatest leader in the world"

"President 'so-and-so' is the greatest man in the world"

"President 'so-and-so' is the most important man in the world"

"President 'so-and-so' is the most powerful man in the world"

Never affirm something you cannot either prove from your research or substantiate with official pronouncements, or with existing and widely-accepted literature.

For example: Be careful with the "Satan-blaming game." If Satan were responsible for every sinful action in the world, nobody would be guilty of anything. To use Satan as the cause of all problems is a "cheap" escape, and may shed a negative light in college writing. Unless you can prove that his name is on the payroll of Budweiser, Phillip Morris, or some drug cartel, you cannot blame him directly for either alcohol, tobacco or drug production, marketing, or addiction.

(Note: The scriptures (James 1:13-15; D&C 10:20-24; 89:4) suggest that Satan merely appeals to the fallen seeds that naturally exist in the hearts of all mortals. He is guilty of "insurrection," while we ourselves become guilty when we misuse our agency.)

Notice the official (i.e. accepted) format for the following terms:

The name of the Church should be used as outlined by the First Presidency in a letter dated February 23, 2001:

- Latter-day Saints (small "d")

- the Church

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- The Church of Jesus Christ

Members of the Church may be appropriately referred to by the following shortened terms:

- Latter-day Saints

- Mormons

The First Presidency discourages the use of the following terms:

- The Mormon Church

- The LDS Church

- The Latter-day Saints Church

Take the time to spell the names of LDS (and other) General Authorities correctly.

Always keep in mind that your score in an exam or your final grade in a religion class has no correlation whatsoever with either the strength of your testimony, your potential for future Church service, or your chances to enter the celestial kingdom.

If you think of additional items to add to this list, feel free to share them with me:

Dr. Marcus H. Martins

BYU-Hawaii, Box 1975

Laie, Hawaii 96762

E-mail: martinsm@byuh.edu

2. Once again, remember that these lists are not meant to be exhaustive.